SPOILED FOR CHOICE.

“Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.”

Oscar Wilde

Pooled investment funds, where investors combine their assets to achieve a common purpose, are a relatively recent phenomenon. The first mutual fund arrived to little fanfare in 1924. No one had heard of private equity or hedge funds before the 1940s and the first ETF launched with just $6.5 million in 1993. Each began as a solitary fund with only a handful of investors, and few predicted they’d evolve into multi-trillion-dollar industries.

Profit attracts innovators and because the finance industry has yet to find something it couldn’t sell, the number of funds has multiplied like bacteria in a college dorm room. Today, there are more equity funds than common stocks, which I’ve always fund a bit of a head scratcher. It’s akin to a sports league with more teams than players.

What’s even more curious is that as products have proliferated, they’ve become less differentiated, not more. Two measures of uniqueness, active share and tracking error are in steady decline and correlation across managers has risen. Half of our assets are now passive, and the industry is rife with closet-indexers. This leaves investors a Hobson’s Choice of ‘average’ or ‘average for a fee.’

I’m keenly aware that few of you are underserved when it comes to financial services. Yet despite this cacophony of oversupply, or perhaps because of it, I chose to create Epigram Capital Partners Fund I.

This begs an obvious question; how could this fund possibly be different? In my more precious moments, I like to think it defies description, but when pressed, I usually call it opportunistic. This term is a broad catch-all for managers who bristle against the conformity of style boxes.

The fund focuses on special situations, where complexity presents the kind of opportunity that often goes uncaptured by a spreadsheet. I recognize this less than satisfying, so using the broadest of brushes, I’ll try to explain what I look for.

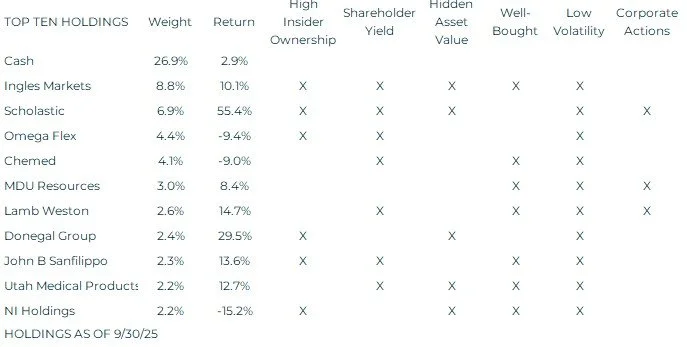

· Small and mid-cap (SMID) companies

· High insider ownership

· Shareholder yield

· Hidden asset value

· Attractive entry

· Low volatility

· Activist involvement, spin-offs and other corporate actions.

SMID: You’ve heard me say that small caps are one of the least efficient parts of the market and its managers more likely to outperform. Because the universe is broad relative to the amount of capital it can absorb, mispricing is frequent and volatility can work in your favor.

HIGH INSIDER OWNERSHIP: 38% of the fund’s holdings have a controlling shareholder or dual share class. Corporate governance experts frown upon this as they view entrenched management as a barrier to value creation that lowers liquidity, since not all the stock floats. While there’s much to be said for professional management, if you’re looking for managers who think like owners, it helps to start with those who actually are.

SHAREHOLDER YIELD: 32% of holdings have a shareholder yield greater than 4% (the sum of buybacks and dividends, divided by market capitalization). Many companies have limited growth potential and it’s easier for an average business to create value by returning capital than by trying to be something it’s not.

HIDDEN ASSET VALUE: The two stocks I’ve written up (Ingles Markets and Scholastic) have sizable real estate holdings relative to their market capitalization. 29% of the fund’s holdings have some form of hidden asset value, which often limits downside.

ATTRACTIVE ENTRY: The primary advantage of being a small fund is nimbleness. I relish buying from a disappointed seller and it’s not uncommon for the fund to establish a full position in a single trading day. 51% of the fund’s holdings have a cost basis within 15% of their 52-week low. Large funds with persistent inflows are rarely as price sensitive.

LOW VOLATILITY: The fund’s objective is two-fold; deliver attractive returns and take less risk while doing it. Many of the industries I cover have low economic sensitivity, which lowers the chance of mistiming the cycle. I don’t screen for beta per se, but by focusing on consistently profitable dividend payers that are conservatively financed, returns can’t help but be less volatile than the benchmark.

If you were to try and shoe-horn these holdings into a style box, they’d neither be growth, nor value, neither quality nor junk. They would screen low volatility, even though many of their shares have fallen considerably. They consist of grocery stores, children’s book publishers, flexible metal hose manufacturers and two of North Dakota’s six public companies. Taken separately, they seem disparate with little overlap. Taken together, they have shareholder friendly managements, high capital returns, multiple levers to create value and were purchased cheaply relative to their history.

I prefer to let the consultants decide how to categorize the fund. But if you’re interested in a fund that bears little resemblance to the rest of the market, and has delivered attractive returns while taking less risk, I’d welcome a conversation.

Sincerely,

Dan Walker