AFFORDABILITY CRISIS.

“Let your home be your mast and not your anchor.”

Kahlil Gibran

Did you know more Americans own a home than invest in common stocks? Or that our nation’s 85 million single family homes are worth roughly as much as the entire stock market? While AI gets all the press, housing’s contribution to the economy is more than twice that of the tech sector (but don’t tell Claude, it might hurt his feelings).

I’m sure you’re aware there’s an affordability crisis and buyers and sellers can’t seem to agree on a market-clearing price. I’m hardly a libertarian, but you can’t discuss home prices without mentioning those kind folks in Washington, DC. While I’m sure they’re well-intentioned, history shows most housing policy is accompanied by a large helping of unintended consequences.

Perhaps an example: in the 1980s, our Education Secretary coined a term called the Bennett Hypothesis. Congress had recently expanded Pell Grants and raised student loan borrowing limits, intending to expand access to higher education. Because students had more borrowing capacity, universities responded by raising tuition. Paradoxically, this made degrees less attainable, not more.

His point was that incentives often distort and that’s especially true of housing. After two decades of interest rate suppression and the nationalization of Fannie and Freddie, housing fundamentals have never been more decoupled from reality. Today, an average home costs five times the median income, close to an all-time high. It’s telling that the three industries the government incentivizes most (healthcare, housing and education) all exhibit the highest rates of inflation.

While it was difficult to say how much COVID stimulus was necessary, no one has accused the Federal Reserve of underdoing it. I refinanced my home in January 2021 with a 2.65% 30-year mortgage, and since the interest is tax deductible, my effective rate is even lower. Inflation has averaged 3.1% since it was first tracked in 1913, so why would a rational actor lend for three decades at a rate almost certain to lose purchasing power?

They did it because the Federal Reserve bought $1.4 trillion of mortgage-backed securities between March 2020 and April 2022, likely including mine. I don’t want to sound ungrateful, but their largess had consequences. A few statistics:

2020 2025 % CHANGE

Value of US Homes $36.2T $55.1T 52%

Median Home Price $327,000 $415,000 27%

Total Monetary Supply $15.4T $22.3T 45%

Average Mortgage Rate 3.1% 6.3% 103%

Median Mortgage Payment $1,068 $2,259 111%

Median Income $67,521 $83,730 24%

Existing Home Sales 5.6m 4.1m (27%)

If you’re like me, you’ve probably checked Zillow to see what your home is worth, congratulated yourself on your savvy purchase and created a psychological wealth effect in the process. Many sellers remain anchored to 2021 prices, ignoring that with today’s rates, few can afford them. This has created a lock-in effect and reduced home sales to levels not seen since 2010.

I count 39 housing stocks in the Russell 2000 and that ignores REITs, banks, home improvement stores and furniture retailers. Many are excellent businesses, but almost all rely on Americans’ willingness and capacity to spend on their homes (which aren’t always the same thing). Last month, I disclosed that Omega Flex (OFLX) was the fund’s third largest position, and I suspect few of you have heard of it.

Omega Flex makes flexible metal hose and piping systems, including TracPipe® corrugated stainless steel tubing (CSST) which is primarily used to transport natural gas in residential buildings. If you own a home built after 1989, and have a natural gas or propane furnace, stove or water heater, you may have their product in your basement (feel free to check). Historically, natural gas lines were encased in rigid black iron pipe, which is durable, but expensive and a pain to install. Omega Flex’s CSST can change directions without a joint, and can be installed in a fraction of the time, yielding substantial labor savings. Consequently, CSST now accounts for half of all new gas connections.

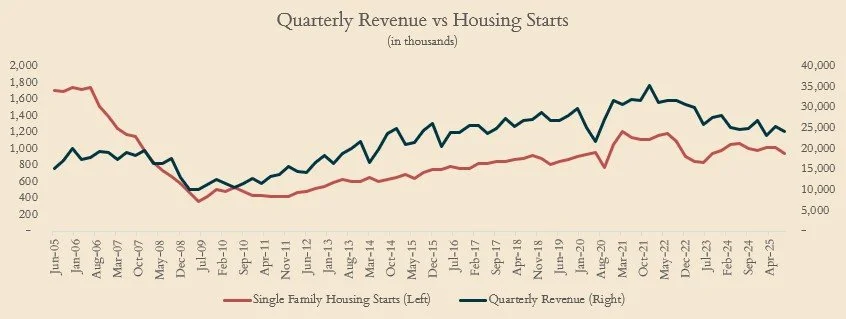

Of course, few of us install a natural gas line for fun, so their revenue (and stock price) is sensitive to new housing starts. Given the affordability dynamic, homes are selling like whatever’s the opposite of hot cakes. Foot traffic is down, cancellations are high and unsold inventory is piling up. While it’s easy to blame mortgage rates, many builders will buy your mortgage below 5% simply to move inventory. The real culprits are price and confidence. A new home is the most discretionary of purchases and consumer confidence is near a 50-year low.

In past letters, I’ve discussed my cautious stance on the economy and general concern for the health of the US consumer. The few discretionary stocks the fund owns provide things like funerals and oil changes, two services I deem fairly nondiscretionary. Omega Flex obviously doesn’t fit with this worldview, and I’d like to explain why.

Omega Flex went public in 2005, right at the peak of the housing market. Despite poor timing it would appreciate more than 1400% over the next fifteen years and when dividends were included, returned almost 23% a year (not an easy feat, considering this included the worst housing crash of our lifetimes). Since housing peaked in 2021 revenue has declined four consecutive years and the stock has lost 85% of its value. Many of its valuation metrics are approaching levels last seen in 2009 and it has never been this cheap on price-to-book.

Despite this economic sensitivity, Omega Flex is a wonderful business. Equity investors often seek out companies with operating leverage, where a small change in revenue yields a large change in earnings. What they ignore is that operating leverage cuts both ways and if you have high fixed costs, a modest sales decline can quickly turn black ink into red. Many building products companies have high operating leverage and earnings often wax and wane along with housing demand.

Omega Flex is the inverse. Thanks to its low fixed-cost structure, it still had 50% gross margins in 2009. Even at these depressed levels, it earns 20% on invested capital, has no debt, almost $5 a share in cash and a dividend yield approaching 5%. Unless we mandate that all future appliances must be electric, which has been tried and failed, this company is extremely hard to kill.

There are three reasons why small cap companies remain small caps. Either they’re cyclical, have a small addressable market, or are low quality, sometimes all three. While Omega Flex is guilty of the first two, it’s among the highest quality small caps I can find. Compared to its $27 share price, it has paid over $19 per share in dividends.

I’m not suggesting that I think new home sales are likely to improve in the near term, in fact I fear the opposite. But longer term, the US has substantially underbuilt demand and I’m confident that Omega Flex’s earnings will be higher five years from now. The dividend is well-covered by earnings power and excess cash, insiders own 65% of the company and while earnings may decline further, the stock is down 86%, discounting some bad news.

But the real kicker is that flexible metal hose was added to the list of derivate steel products covered by Section 232 tariffs in August. Given the small market, it’s difficult to ascertain what percentage is supplied by imports, but if you look up CSST on Amazon, you’ll see low-cost Chinese competitors. These are now subject to a 50% tariff, which means that even if new starts stay depressed, Omega Flex could grow through market share, pricing or both. Given natural gas is both toxic and flammable, I’m not sure that’s a corner I’d be looking to cut. The majority of black iron pipe is also imported, further widening their pricing advantage. And even in the worst housing market of our lifetimes, the US still built 400,000 new homes in 2009.

Cyclical investing is difficult to time and Omega Flex has been down four years in a row. The fund purchased shares at prices similar to 2015 and I fully recognize that I may be early. But the best test of conviction is a willingness to tolerate underperformance. If a stock declines 20% and your first inclination is to sell, you may want to stick with fixed income investing. Buying a great business when it’s down 85%, has no balance sheet risk and earning 5% while you wait for a recovery strikes me as a compelling risk-reward ratio.

Sincerely,

Dan Walker