FALSE URGENCY.

“Slow is smooth. Smooth is fast.”

US Navy SEAL Adage

In my last year of business school, against my better judgment, I began training for my first marathon. Between getting an MBA, managing a portfolio, interviewing for jobs and trying to earn a CFA® charter, there obviously wasn’t enough on my plate. While the marathon will never be my favorite distance, I got hooked on competing and have finished 57 races since.

Toe enough starting lines and you’ll come to appreciate two things. The first is that race directors will use every means at their disposal to energize the crowd. The second is that pre-race jitters are universal, even among experienced runners. These phenomena are not unrelated. You try staying calm near a vuvuzela.

Starting lines are the ultimate bottleneck and getting thousands of participants through an inflatable arch without trampling each other is a logistical feat. The first quarter mile of any course is always the most congested, and racers can stumble, trip or even collide midstride. It’s a bit like Pamplona minus the bull.

So it’s no surprise that race day nerves hit first-timers hardest. They’ve spent months in preparation and adrenaline inevitably does its thing. In most races, the newbies go out too fast leaving the rest of us to wonder if hell isn’t missing a bat. We veteran runners recognize their pace is unsustainable long before they do, but everyone gets to run their own race, so it’s best if you don’t bring it to their attention when you pass them huffing on the side of the road at mile three.

Said differently, runners are just like the rest of us, excitable and prone to over-confidence especially when trying something new. Recognizing this behavioral quirk, seasoned runners take a deep breath, keep their heart rate low and run their first mile slower than they’re capable. Or at least I do.

By now, you’re probably wondering what this has to do with investing. As I close the books on Epigram Capital’s first year, this is a fair analogy for how I’ve chosen to scale. My goal was to be intentional and deliberate when deploying your capital because the investors I admire never seem to be in a hurry. If given the choice between a reputation for excessive prudence or excessive recklessness, I know which I’d prefer. Plenty of first-time managers fizzle out of the gate, and like all good distance runners, I hope to be judged by the totality of my performance, not my first mile pace.

In my experience, good performance seldom requires explanation while underperformance often does. Trailing managers tend to overexplain, which to my ear usually sounds like an excuse. But since the fund is scaling during a rather unusual market, I was hoping you’d indulge me.

In my October letter, I mentioned that the timing of a fund’s launch leaves much to chance and that new funds frequently top pick the market (as that’s when it’s easiest to raise capital). I call this inception risk and the only way I know to mitigate it is to invest over time. I count friends, neighbors and relatives among my partners and care more about capital preservation than squeezing every last drop of return from a frothy market. Consequently, the fund has averaged 44% cash in its first year. This is unlikely to be the case going forward.

Secondly, I’d like to discuss flows. A quirk of performance reporting is that funds report time-weighted returns rather than dollar-weighted returns, the logic being that a manager doesn’t control inflows and shouldn’t get credit for them. This means that when a fund gets new capital, it often blindly buys what it owned yesterday, regardless of price. Because the incremental capital is usually a small percentage of total assets, they’re indifferent to that investor’s specific return because it goes unreported in marketing materials. This anomaly is well-documented, and studies show the average investor’s return consistently trails a fund’s stated performance.

These dynamics are especially complex in a fund’s early years. Epigram Capital’s assets grew 380%in 2025 and in a rising market, dollar-weighted returns usually trail time-weighted ones (since you’re receiving capital after the market has risen). In the case of Epigram, the fund doubled in July after a 24% surge.

Because I’ve been price sensitive in my deployment and as the impact of cash moderates, my dollar-weighted returns (the ones my investors have actually earned) exceed my time-weighted returns by more than 2%, meaning as the fund has grown, returns have gotten better. In running parlance, this is akin to negative splits (when you run each subsequent mile faster than the last). I’d be thrilled if that were always the case.

Next, I’d like to discuss benchmarks. The majority of small cap managers use the Russell 2000 as their primary index. As previously mentioned, 42% of the index is unprofitable which isn’t a great fit for my process, but I chose it due to industry familiarity and convention. The remainder use the S&P 600 Small Cap Index which requires profitability but hasn’t been around as long. It also excludes many smaller companies where I see substantial upside. Alas, no index is perfect.

Like I said, this year has been unusual. From the Inauguration to Liberation Day, the Russell 2000 fell 24% (one of the quickest selloffs outside COVID). Subsequently, thanks to AI enthusiasm, tariff reprieves, falling interest rates and tax cuts, it has risen 42%. But I would caution that this performance has overwhelmingly come from unprofitable stocks, which are up almost 75%. The 100 best performing companies in the Russell 2000 since April 8th are up a staggering 383% on average, only 17 of which are profitable. In roughly eight months, 116 stocks have tripled and 313 have doubled. I don’t spend much time in casinos, but I know gambling when I see it.

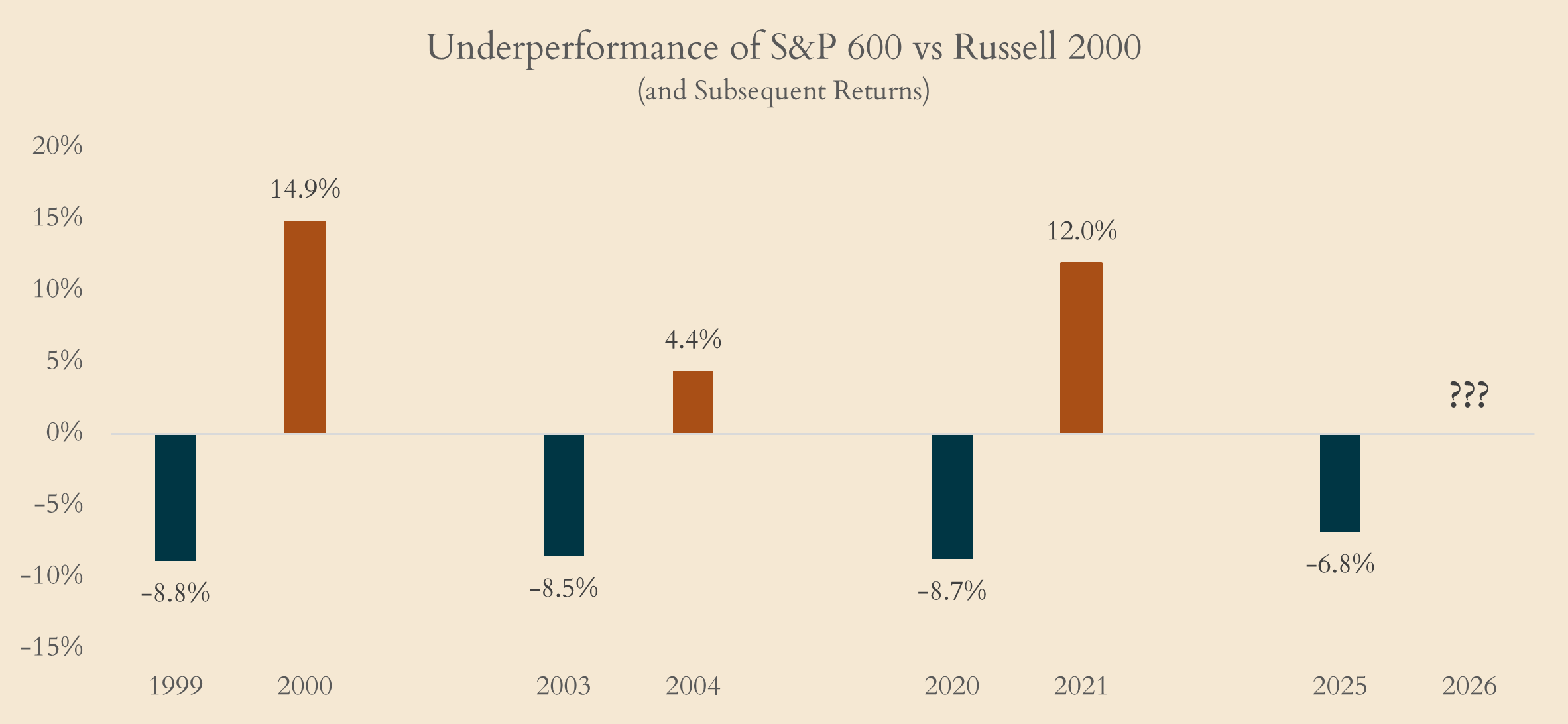

The S&P 600 trailed the Russell 2000 by almost 7% this year, its fourth worst showing ever. All three prior examples were years when the Fed cut interest rates, as they did three times this year. In every subsequent year, the S&P 600 outperformed, often dramatically. I have no idea if 2026 will repeat the pattern, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

You needn’t fret. I’m not changing my benchmark just because the comparison happens to be more flattering. But I think history will back me up when I say that over any reasonable length of time, profitable companies will outperform unprofitable ones. Since 1994, the S&P 600 has outperformed the Russell 2000 by more than 700%. There are periods where investors deliberately seek risk, usually when rates are falling, liquidity is improving or economic fear is abating, i.e. now. A manager can try to time those years, but they rarely last for long.

Despite trailing my chosen index, I’m not dissatisfied with the fund’s first year performance. Cash has averaged 44% since inception, yet the fund still managed to keep up with the S&P 600. The stocks I’ve purchased are up 14% year-to-date in a year when the median stock in the S&P 600 is down. The max drawdown of -5% compares favorably to the Russell 2000 at -24%. You’ll be the ultimate judge, but if your goal is to deliver respectable absolute returns with less downside than the market, as mine is, I believe the fund is meeting its objectives.

Lastly, I want to express my gratitude to the Founding Class of Epigram Capital Partners Fund I. Regardless of track record or pedigree, taking a chance on an emerging manager will always be a tough sell. I began the year working beneath a bowling alley with five limited partners and $2.5 million in assets. I’m ending the year with 19 LPs and $12.5 million in assets. Thanks to the generosity of a family office that has a fondness for strays, I now have office space that reflects my ambitions.

This wouldn’t be possible without your endorsement. Omaha’s affluent have been beyond generous with their time, encouragement and support. While plenty of fund managers think they’re hot stuff, I recognize all the investment talent in the world isn’t worth much until someone trusts you with their capital. It’s not a charge that I take lightly and you have my sincerest gratitude.

Sincerely,

Dan Walker